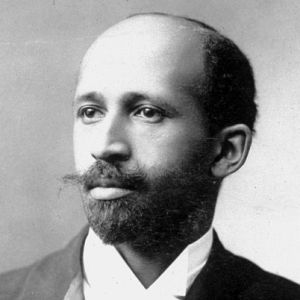

Scholar and activist W.E.B. Du Bois was born on February 23, 1868, in Great Barrington, Massachusetts. In 1895, he became the first African-American to earn a Ph.D. from Harvard University. Du Bois wrote extensively and was the best known spokesperson for African-American rights during the first half of the 20th century. He co-founded the NAACP.

Scholar and activist W.E.B. Du Bois was born on February 23, 1868, in Great Barrington, Massachusetts. In 1895, he became the first African-American to earn a Ph.D. from Harvard University. Du Bois wrote extensively and was the best known spokesperson for African-American rights during the first half of the 20th century. He co-founded the NAACP.

Below is a short bibliography of writings related to Du Bois and spirituals.

Brooks, Christopher A. “The ‘Musical’ Souls of Black Folk: Can a Double Consciousness Be Heard?” InThe Souls of Black Folk One Hundred Years Later,edited by Dolan Hubbard, 269–83. Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 2003.

Examines Du Bois’s use of spirituals in The Souls of Black Folk (1903). A study of Du Bois’s life makes clear that he moved with apparent ease through two worlds—black and white, a double consciousness—and had a musical affinity for several traditions. While Du Bois’s musical diversity is not hard to understand, his interest in politicizing the spiritual as others had and incorporating it in such a scholarly way in Souls at the turn of the twentieth century was unique and innovative. (Author’s abstract, revised)

Carroll, Anne. “Music and Poetry: Representing Two Cultures in the Souls of Black Folk.”In Process: A Graduate Student Journal of African-American and African Diasporan Literature and Culture1 (Fall 1996): 124–42.

Discusses the way Du Bois juxtaposes Western poetry and African-American spirituals. Du Bois begins each chapter in The Souls of Black Folk (1903) with a short poem by a prominent European American author, demonstrating that African-American and European American traditions are complementary rather than at odds. Carroll maintains that Du Bois is redefining American culture to reflect the contributions of the country’s African American as well as European American citizens.

Dennis, Rutledge. “Du Boisian Thought in Contemporary America: From Double Consciousness to Dual Marginality.”National Political Science Review13 (2012): 79–90.

Examines, in detail, the philosophy behind the work of W. E. B. Du Bois. Du Bois staged a remarkable social and psychological revolution in American thought with the publication of The Souls of Black Folk (1903). The book guided the reader through a brief history of race relations in the nation. The revolution he staged entailed a deep structural analysis of the hierarchical role of color, race, and class in American society. Briefly mentions spirituals. (Publisher’s abstract, revised)

Du Bois, W. E. B. “Of the Sorrow Songs.” InThe Negro in Music and Art,edited by Lindsay Patterson, 9–14. New York: Publishers Co., 1968.

A reprint of chapter 14, “The Sorrow Songs,” from The Souls of Black Folk (1903). For Du Bois, the sorrow songs represented a black folk culture, with its origins in slavery. While some believed that the songs should be purged from the cultural repertoire, Du Bois passionately advocated for the preservation of the spiritual.

Herring, Scott. “Du Bois and the Minstrels.”MELUS22, no. 2 (1997): 3–17.

Concerns Du Bois’s The Souls of Black Folk (1903), where the first comprehensive analysis of “sorrow songs,” later known as spirituals, was discussed. Du Bois discusses the removal of spirituals from the original setting of the plantation or church to the stage. By re-appropriating spirituals for use by groups such as the Fisk Jubilee Singers, a distinctively African-American art form was created. This opened the door to the Harlem Renaissance.

Radano, Ronald Michael. “Soul Texts and the Blackness of Folk.”Modernism/Modernity2, no. 1 (1995): 71–95.

Discusses double consciousness as developed in W. E. B. Du Bois’s The Souls of Black Folk (1903). Du Bois studied at Fisk University in Nashville, and music’s prominent role at Fisk is also evident in Du Bois’s writings, which include notated incipits of sorrow songs. Fisk’s Jubilee Singers formed immediately after the Civil War, and transcriptions of the Jubilee Singers’ repertoire influenced figures such as Mark Twain and Antonín Dvořák. Du Bois was acutely aware of the interracial signification from which African-American musical culture emerged in late nineteenth-century United States.

Weheliye, Alexander G. “The Grooves of Temporality.” Public Culture 17, no. 2 (2005): 319–38.

Examines W. E. B. Du Bois’s The Souls of Black Folk (1903) as a model of modern African-American temporality and cultural practice rooted in and routed through sound. While Souls blends together history, eulogy, sociology, personal anecdote, economics, lyricism, ethnography, fiction, and cultural criticism of African-American music, Du Bois’s central aesthetic achievement in this text appears in bars of music placed before each chapter. Du Bois’s use of spirituals calls into question their representability in the Western system of musical notation while pointing to the limits of the method itself. As a result, the spirituals mirror Du Bois’s own double textual strategy, which mixes “major” and “minor” cultural archives as opposed to merely using one to mimic the other. (Author’s abstract, abridged)