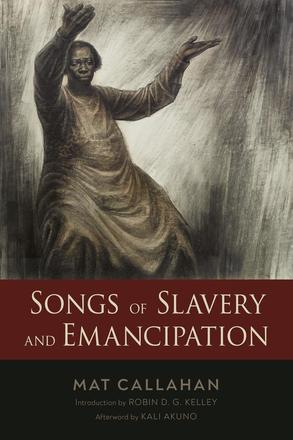

By Mat Callahan

Mat Callahan presents recently discovered songs composed by enslaved people explicitly calling for resistance to slavery, some originating as early as 1784 and others as late as the Civil War. He also presents long-lost songs of the abolitionist movement, some written by fugitive slaves and free Black people, challenging common misconceptions of abolitionism. Songs of Slavery and Emancipation features the lyrics of fifteen slave songs and fifteen abolitionist songs, placing them in proper historical context and making them available again to the general public. These songs not only express outrage at slavery but call for militant resistance and destruction of the slave system. There can be no doubt as to their purpose: the abolition of slavery, the emancipation of African American people, and a clear and undeniable demand for equality and justice for all humanity. See at the University of Mississippi Press website