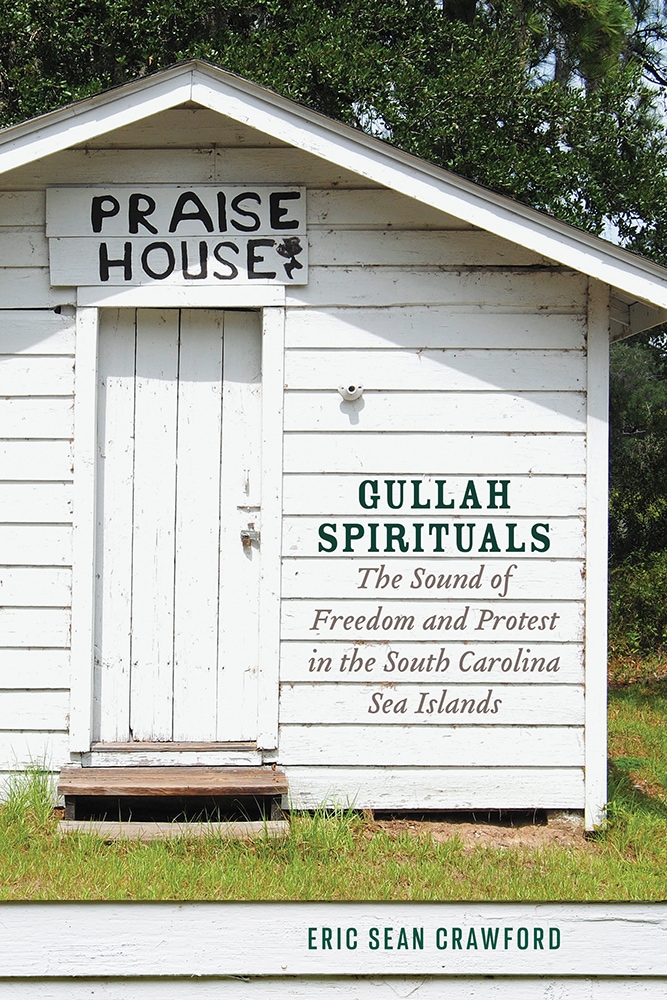

The Sound of Freedom and Protest in the South Carolina Sea Islands

In Gullah Spirituals musicologist Eric Crawford traces Gullah Geechee songs from their beginnings in

West Africa to their height as songs for social change and Black identity in the twentieth-century American South. While much has been done to study, preserve, and interpret Gullah culture in the Lowcountry and sea islands of South Carolina and Georgia, some traditions like the shouting and rowing songs have been all but forgotten. This work, which focuses primarily on South Carolina’s St. Helena Island, illuminates the remarkable history, survival, and influence of spirituals since the earliest recordings in the 1860s. Read more

Deacon James Garfield Smalls is 98, but he’s still got a boombox inside that rumbles out spirituals he learned from his great-grandfather on St. Helena Island.

Deacon James Garfield Smalls is 98, but he’s still got a boombox inside that rumbles out spirituals he learned from his great-grandfather on St. Helena Island. 8): 11–14.

8): 11–14. to Fisk University and the Jubilee Singers, this article discusses the early history of the Cotton Blossom Singers at Piney Woods Country Life School in Mississippi from about 1921 to the 1940s. Locally, the group was known as the Piney Woods Singers. Their travels, repertoire, radio programs, and their encounters with racism are discussed. A day-by-day account in one week of travel is included. (Author’s abstract, slightly revised)

to Fisk University and the Jubilee Singers, this article discusses the early history of the Cotton Blossom Singers at Piney Woods Country Life School in Mississippi from about 1921 to the 1940s. Locally, the group was known as the Piney Woods Singers. Their travels, repertoire, radio programs, and their encounters with racism are discussed. A day-by-day account in one week of travel is included. (Author’s abstract, slightly revised)